PLANTS

A resilient landscape is fire-wise, water wise and promotes biodiversity by using California native plants. These gardens use sustainable practices, plant selection, and maintenance to reduce the risk of fire in the defensible space zone. Resilient gardens save water, protect us from fire and promote biodiversity.

Plant Selection

Plant Selection: “Right plant, right place”

After reviewing the guidance in the Landscapes section, select plants using the following guidelines:

- Size and shape. Choose plants that will mature at the desired height and width, reducing or eliminating the need to prune to control their size.

- Site conditions will refine your plant selection. Consideration of slope, exposure, and wind will allow you to match the best plants to your unique situation. Be aware whether a plant prefers sun or shade, and its tolerance of different soil types and drainage. In choosing plants, it also helps to know the local plant communities of your watershed.

- Plant type. Consider whether the best plant for the site will be a ground cover, a shrub, an herbaceous perennial, or a tree. These different plant types will have different roles to play in the defensible space, as described in the Landscapes section.

- Native plants provide many more resources to our native pollinators and other wildlife than non-native plants, and are an important source of habitat. A mix of at least 80% native plants provides excellent habitat for wildlife biodiversity, and allows plenty of room for other favorites.

- Climate adaptation. Choose from plants that are well adapted to a summer dry climate, and that won’t suffer from your area’s temperature extremes in summer and winter. The goal is to choose plants that will be healthy with the least water and maintenance.

- Variety helps to create a beautiful garden and provides many resources to wildlife. Strive for a diverse planting with plants that bloom throughout the year, while utilizing some massing of three or more plants of the same species to create some continuity.

Plants and Fire

Remember that the condition of the plant is often as important as the species. Many plants that are considered fire hazardous can be beneficially used in the garden if properly maintained and irrigated, especially natives. Depending on its maintenance, growth form and access to water, the same plant may be ignition resistant in one environment and flammable in another. All water-stressed plants in poor condition are more likely to burn readily.

For this reason, and because all plants can burn, we don’t recommend use of a “fire-safe plant list”, as this can lead gardeners to a false sense of security. There are, however, certain plant species that create a lot of fine debris and are difficult to maintain. These plants would ideally be removed from the Defensible Space area and replaced with less problematic plant selections. Some characteristics that tend to make plants more fire hazardous include:

- gummy, resinous sap with a strong odor

- A fine, twiggy growth habit

- loose or papery bark

We recommend that plants with these characteristics are avoided or used with caution.

Recommended Plants

Groundcovers

| California fuchsia Epilobium species and cultivars |

Bearberry Arctostaphylos uva-ursi |

|

California fuchsia, photo by Jon Kanagy California fuchsia, photo by Jon Kanagy |

Bearberry, photo by Jon Kanagy Bearberry, photo by Jon Kanagy |

|

| The California fuchsia groundcover cultivars such as ‘Wayne’s Silver’ and ‘Schiefflan’s Choice’ are showy perennial groundcovers, with gray-green foliage, to about 1 ft. tall. The bright orange-red tubular flowers attract hummingbirds in the late summer to fall. | Bearberry is a mat-forming evergreen groundcover growing 6-18 in. tall and 6-8 ft. wide. It prefers part shade and grows rapidly near the coast where it can take more sun. This valuable habitat plant blooms in early winter with white or pale pink urn-shaped flowers and is covered in showy red berries in the fall. Bearberry is a good choice for erosion control and for under oaks. If appropriately spaced this lovely groundcover will need no maintenance. | |

| California Lilac Ceanothus species and cultivars |

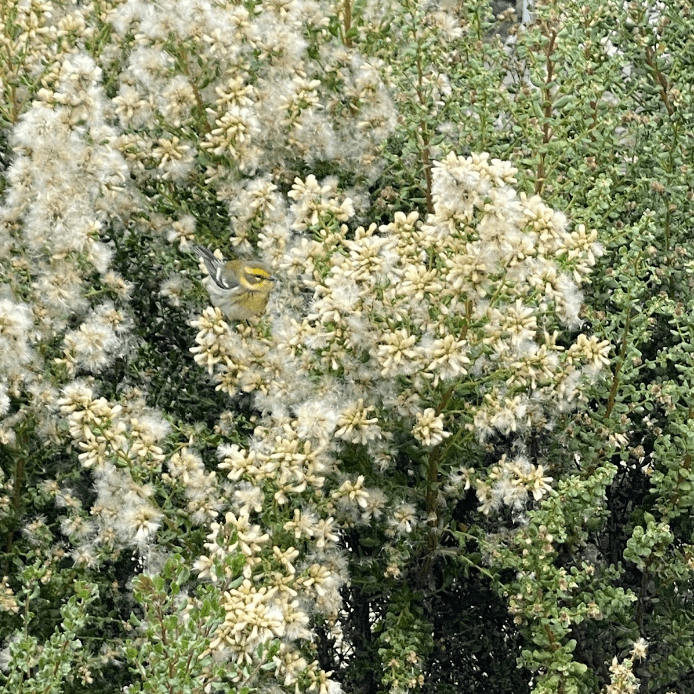

Coyote Brush Baccharis pilularis cultivars |

|

Yankee Point Groundcover Ceanothus – photo credit Pat Sesser Yankee Point Groundcover Ceanothus – photo credit Pat Sesser |

Coyote Brush Groundcover – photo by April Owens Coyote Brush Groundcover – photo by April Owens |

|

| Ceanothus groundcover species most commonly occur along the California coast. Ceanothus thyrsiflorus var. griseus or Ceanothus gloriosus ‘Anchor Bay’ are available in nurseries. This beautiful and drought tolerant evergreen groundcover grows from 8-24 in. tall, depending on the cultivar. | Baccharis cultivars ‘Twin Peaks’ and ‘Pigeon Point’ are evergreen groundcovers that can grow 12-18 in. tall to 6 ft. (or more) in width within a few years, so be sure to space appropriately. These groundcovers naturally occur along the entire California coast. They have a deep root system that provides good erosion control, and they can take a lot of pruning as needed. For fire-wise planting, pruning should be done every few years to keep plants from becoming too woody. | |

| Wild Strawberry Fragaria species |

Lippia Phyla nodiflora |

|

Beach strawberry, photo by Jon Kanagy Beach strawberry, photo by Jon Kanagy |

Lippia, photo by April Owens Lippia, photo by April Owens |

|

| This shade loving groundcover spreads quickly to cover 3 ft. or more and is only 3 in. tall. Woodland strawberry (Fragaria vesca) occurs in redwood forests, and beach strawberry (Fragaria chiloensis) occurs in coastal plant communities. Both form dense groundcover carpets with fire-wise value, and both plants appreciate monthly irrigation in the summer. | Lippia is a spreading ground cover that is tough and walkable and able to survive a wide range of conditions and soil types. Best with occasional deep watering in full sun to very light shade, lippia can be used as a lawn replacement that looks best in summer. Bees and butterflies are attracted to its small pink and purple flower blossoms. |

Perennials

| Sage | ||

| Salvia species | ||

Sonoma sage, photo by April Owens Sonoma sage, photo by April Owens |

Hummingbird sage, photo by April Owens Hummingbird sage, photo by April Owens |

|

| Sages come in all shapes and sizes from groundcovers like Salvia sonomensis (Sonoma sage) to Salvia clevelandii (Cleveland’s sage), a 4 ft. x 4 ft. flowering perennial. Salvias bloom in the spring with an abundance of purple to blue flowers that attract hummingbirds, butterflies and bumblebees. Natural oils give them their characteristic scent, which also can make them flammable. Maintain by cutting back by two-thirds annually to encourage lush foliage. Hydrate in the summer in warmer inland gardens. | ||

| California Fuchsia | California buckwheats | |

| Epilobium canum | Eriogonum species and cultivars | |

|

|

|

| Epilobium canum is a beautiful late summer blooming perennial that is native to California foothills and coastal areas. California fuchsia is notable for the profusion of bright scarlet flowers in summer and autumn, blooming when many other perennials have finished. This perennial tends to die back and go dormant in the winter. Easy to grow, California fuchsia will flower most profusely in full sun. In the wetter, northern part of its range or near the coast, this plant will typically require no supplemental water after establishment. It can be watered once a month, generally, without harming the plant. By late fall or early winter, plants tend to get straggly, but if cut back to the ground as soon as the flowers are spent, they will come back lush and healthy in the spring. One of the best native plants for attracting hummingbirds. | The genus Eriogonum is one of the most diverse in the California flora and provides native plant gardeners with a wealth of beautiful plants of varying form and color. Eriogonum fasciculatum forms a shrubby mound to 3’ tall and 4’ wide, though the cultivar ‘Warriner Lytle’ tops out at only half the height. Eriogonum grande var. rubescens is a perennial to 18” with lovely rose-pink flowers, while Eriogonum umbellatum features yellow flowers on a similarly sized plant. All of the California buckwheats have clusters of tiny flowers that are very attractive to pollinators, and are followed by seeds eaten by birds. | |

| Monkeyflower | Coyote Mint | |

| Diplacus species and cultivars | Monardella villosa | |

A monkeyflower hybrid, photo by April Owens A monkeyflower hybrid, photo by April Owens |

Coyote mint, photo by Jon Kanagy Coyote mint, photo by Jon Kanagy |

|

| This colorful perennial grows to about 2 ft. tall and wide. Diplacus aurantiacus (sticky monkeyflower) occurs all over California from coastal to chaparral communities, and fits well into many landscapes. Monkeyflower browns out in the heat of the summer, but will tolerate some water. Monkeyflower is a food source for hummingbirds, bees and other pollinating insects. Plant in sun to part shade and irrigate monthly in summer after established. There is a broad range of cultivars and hybrids in flower colors from red to white. | Coyote mint grows up to 18 in. tall and 4 ft. plus wide if unpruned. It has a long blooming cycle, flowering through the summer and fall, attracting butterflies and hummingbirds. Songbirds eat the seeds. Cut back to a tight ball bi-annually to maintain lush foliage. | |

Shrubs

| Manzanita Arctostaphylos species |

Coyote Brush Baccharis pilularis |

|

’Howard McMinn’ manzanita, photo by April Owens ’Howard McMinn’ manzanita, photo by April Owens |

Coyote Brush photo by April Owens Coyote Brush photo by April Owens |

|

| Manzanitas are shrubs with huge habitat benefits. With proper maintenance and placement manzanitas, whether as specimens or a grouping, offer great value in the resilient garden. The manzanita berries attract mockingbirds, robins, and cedar waxwings. If unpruned theyprovide cover for quail and wren-tits and the flowers produce nectar for native bees and hummingbirds. Arctostaphylos ‘Howard McMinn’ is rounded in form and profusely branched, growing 3-6 ft. tall. It has shiny green leaves and abundant light pink flowers. Beautiful mahogany trunks create a wonderful sculptural effect. The dense foliage responds exceptionally well to pruning—even shearing, and tolerates a far greater range of soils and watering regimes than most manzanitas. | The upright form of coyote brush, growing 4-8 ft. tall and wide, is valued for its ability to flourish in a wide range of conditions. An excellent habitat plant, coyote brush provides food and cover to a wide variety of wildlife. Flowers are not showy on the male; female flowers are borne on separate shrubs. These plants produce ivory colored flowers with pollen and nectar. An abundance of pollinators and beneficial insects use Baccharis flowers. Plant in sun to light shade; coyote brush is not fussy about soils, and is quite drought tolerant once established. Coyote brush can tolerate hard pruning to keep it fire-wise. The habitat benefit of this shrub is worth some maintenance. | |

| California Lilac Ceanothus species |

Toyon Heteromeles arbutifolia |

|

A California lilac in bloom, photo by April Owens A California lilac in bloom, photo by April Owens |

Toyon berries, photo by Jon Kanagy Toyon berries, photo by Jon Kanagy |

|

| Blueblossom ceanothus (Ceanothus thyrsiflorus) is an evergreen shrub growing from 15-20 ft. tall by 10-15 ft. wide. It prefers full sun to part shade and needs very little water once established. A beautiful purple flowering shrub, blueblossom attracts an array of wildlife including birds, butterflies, bees and other insects. It can be hedged to control size or pruned into a small tree.

‘Concha’ lilac (Ceanothus ‘Concha’) is an evergreen shrub that grows 4-8 ft. tall with stunning, deep blue fragrant flowers in large clusters. ‘Concha’ is more compact than blueblossom ceanothus but has many of the same water and sun needs. ‘Concha’ is considered one of the most reliable and garden tolerant California lilac species. Many species of California native bees are attracted to this plant. Though it can tolerate light pruning, ‘Concha’ should be placed far apart from other plants to minimize pruning. |

Toyon, or Christmasberry, is a moderately fast growing evergreen shrub that is good for screening. It prefers full sun or part shade and needs little water once established, but can tolerate some garden water. Toyon has attractive deep green leaves, produces small white flowers in summer and red berries in winter. This is a great substitute for the invasive cotoneaster for bird habitat and screening. Toyon can tolerate pruning to be more tree-like or can be pruned lightlyas a hedge. | |

| Flowering Currants and Gooseberries Ribes species |

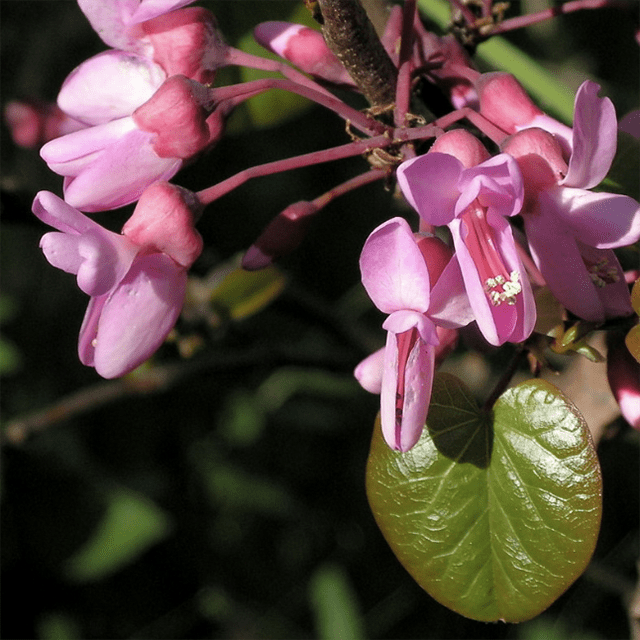

Western Redbud Cercis occidentalis |

|

Flowering currant, photo by Jon Kanagy Flowering currant, photo by Jon Kanagy |

Western Redbud photo Kathi Dowdian Western Redbud photo Kathi Dowdian |

|

| Flowering currants and gooseberries (Ribes species) are a colorful group of shrubs growing 6-8 ft. and blooming in late winter to early spring, providing an important early nectar source for bumblebees and hummingbirds. Flowering currants go dormant in the summer without some water and light shade. Clean off dead leaves that haven’t fallen on their own in August in the fire-wise garden. | Western redbud (Cercis occidentalis) adds seasonality to the California native garden. Revealing its beautiful structure in the winter after losing its leaves, redbud produces beautiful small magenta flowers that cover the stems, attracting hummingbirds, bees, and other pollinators in the late winter. After flowering, redbuds sprout shiny heart-shaped leaves and later in summer are covered in purple seed pods. Redbuds prefer sun or part shade and need no irrigation once established. They grow 10-20 ft. tall and 10-15 ft. wide. Redbuds respond well to overall pruning and shaping in winter. They are native to the Sierra foothills and inner coastal ranges. | |

| Coffeeberry Frangula californica |

Blue Elderberry Sambucus nigra ssp. caerulea |

|

Coffeeberry, photo by April Owens Coffeeberry, photo by April Owens |

Elderberry, photo by April Owens Elderberry, photo by April Owens |

|

| Coffeeberry is an evergreen shrub with dark green foliage that can grow up to 15 ft., but more compact selections like ‘Mound San Bruno’ grow to 5 ft. tall by 6 ft. wide. Small, greenish-white flowers in spring are very attractive to pollinators, and are followed by black fruit relished bybirds in the fall making coffeeberry a valuable plant for the habitat garden. It tolerates a wide variety of soil types, prefers afternoon shade in interior sites and appreciates some irrigation at most locations. Irrigated monthly in the summer, coffeeberry is a habitat powerhouse and a beautiful fire-wise screening shrub. | Blue elderberry is a very fast growing screening shrub up to 15 ft. tall that can be cut back to the ground every few years to encourage fresh new growth and as a fire-wise practice. It prefers full sun to part shade and tolerates drought once established. However, blue elderberry benefits from some summer moisture and will thrive in a regularly irrigated garden. Blue elderberry has glossy, bright green leaves that provide texture in the garden. The large, flat-topped clusters of creamy white flowers in early summer are a favorite of pollinators and the blue-black berries in late summer are a food source for birds and other wildlife. | |

| Oregon Grape Mahonia aquifolium |

||

The holly-like leaves of Oregon grape, photo by Jon Kanagy The holly-like leaves of Oregon grape, photo by Jon Kanagy |

||

| Oregon grape is an evergreen shrub with holly-shaped glossy leaves that grows 3-7 ft. tall and 6 ft. wide and prefers shade or part shade. It has fragrant, yellow, nectar-rich flowers in winter/spring and dark blue berries in the fall, which can be used for jelly. Give Oregon grape moist, well drained soil. This shrub, which spreads by rhizomes, makes a hedgerow of prickly ground cover for birds and other wildlife. Keep it well irrigated in a fire-wise garden, although this shrub is drought tolerant once established. |

Resources:

California Native Plant Society – The Nature Restoration Approach

Water and Irrigation

Plants vary tremendously in their need for water, both in the amount of water and its timing throughout the year. Even California native plants have different needs, based on the distinct region in which they have evolved. There are many California natives that are well suited to your garden, that generally will have lower water needs than many popular non-native plants. You may search for your address in Calscape to find a list of plants native to your area, and are therefore likely to be well adapted.

Plants vary tremendously in their need for water, both in the amount of water and its timing throughout the year. Even California native plants have different needs, based on the distinct region in which they have evolved. There are many California natives that are well suited to your garden, that generally will have lower water needs than many popular non-native plants. You may search for your address in Calscape to find a list of plants native to your area, and are therefore likely to be well adapted.

Hydration

Before talking about irrigation (providing water for plants), let’s ask ourselves what we can do to support hydration, the maintenance of healthy water levels in the plant. Many plants will require some irrigation, especially as they’re becoming established, but there are many things we can do to minimize the need to irrigate. Remember that what’s important is soil moisture at the root level. The soil surface may be dry even if the roots are properly moist. Check with your fingers or a moisture meter.

Water Conservation

|

|

Start with plants well adapted to your climate and site. | |||

Mulches cover and shade the soil and reduce the loss of moisture to evaporation. Inorganic mulches such as gravel will shade the soil and are appropriate in areas immediately adjacent to the house to protect from fire. However, in the sun they can cause the soil to heat up which may impact beneficial microorganisms. Where Defensible Space guidelines allow, a 2-3” layer of wood chip mulch will keep the soil cool, conserve moisture, and increase organic matter in the soil, which acts as a sponge. Review the section on mulches since wood chips are not appropriate everywhere in the firewise landscape. |

|||||

|

Organic matter in the soil, which can be increased by additions of compost and the natural breakdown of leaf litter and wood chips, will act as a sponge and store water for later use by plants. A specialized form of charcoal called biochar is created by burning woody waste generated by sustainable forest management practices. This material, typically mixed with compost, increases soil health and conserves soil nutrients and water. Learn more here. | ||||

Special landscape features can be created to match the needs of the plants . Creating a mound, or berm of soil will improve drainage on the top and sides. At the base of the mound, more rainwater or irrigation water will accumulate. Likewise, a depression in the soil (a “rain garden” or swale) can be created to hold rainwater and allow it to percolate into the soil. Such retention basins may allow a moister environment for plants that prefer it. |

|||||

|

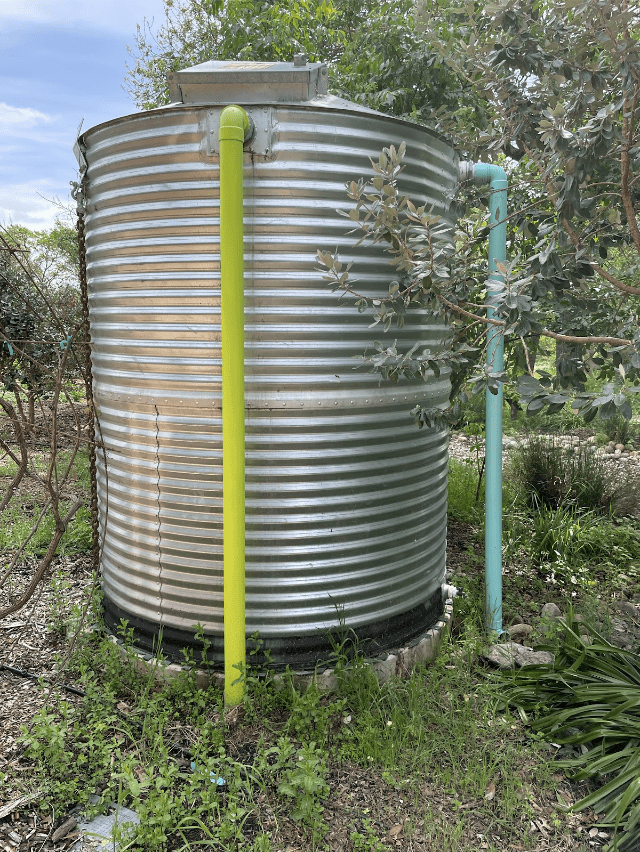

It may be possible to direct stormwater from your roof or other hard surfaces into one or more retention basins in your landscape. Similarly, it may be possible to collect rainwater in barrels or tanks for summertime irrigation use. | ||||

|

|

||||

|

Many municipalities are supportive of greywater use in the landscape, particularly the wastewater from the clothes washer. Check the resources at Daily Acts, and the requirements of your local municipality. | ||||

Turf Replacement

Turf Replacement

Turf grass is one of the most water-intensive plants in your landscape. By replacing your lawn with a native plant landscape, you could save on your water bill, maintenance costs, and show that you care about conserving water. Many cities in Sonoma County offer rebate programs for lawn replacement. Find more information at the Sonoma-Marin Saving Water Partnership.

Irrigation

Irrigation

New plants are best planted in the fall when temperatures are cooler and young plants can use the coming rains to get their roots established. They’ll be much better able to thrive during the coming summer months, but will still need supplemental irrigation to stay well hydrated, and so a minimal fire threat.. The water needs of newly planted native plants will depend on many things, among them: the plant species, what season was it planted (fall, winter, spring, summer), and the type of soil (clay vs. sandy loam, how much organic matter). As the plant becomes more established over a period of 2-3 years, both the interval between watering and the length of time of watering can be increased.

When and how much to water

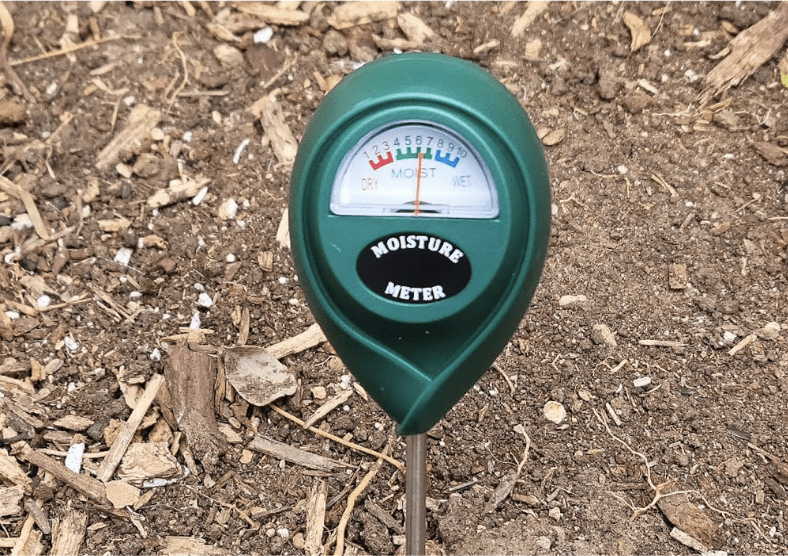

Native plants are adapted to a climate of winter rain and a dry summer. Many California natives will succumb to disease if overwatered. Do not water in the summer if the soil is already moist at root level. An inexpensive soil moisture meter can tell you the soil moisture up to 10” deep.

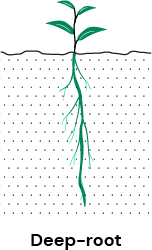

When summer irrigation is needed, water infrequently but deeply. Newly planted natives will likely require irrigations of about 1 gallon of water per plant once or twice weekly during the first summer if planted from a 1 gallon container. In the second summer, 2 gallons per plant twice per month may be a good goal. For many established natives after two years of growing in their garden site, an interval between deep watering of 2-4 weeks is appropriate. Deep watering allows penetration of moisture to around 6-12” of depth. Sometimes, winter rainfall needs to be supplemented with some irrigation if the winter is particularly dry. This will allow the California native to survive the long, dry season ahead.

Soil Conditions

Clay soils have little air space between soil particles. Water that is applied will spread laterally in the soil, and be held longer. Water that is supplied too quickly, as from a garden hose, may run off the surface before penetrating. Sandy soils, on the other hand, have much larger spaces between particles, and water will quickly penetrate without much lateral spread. Sandy soils will also dry more quickly. Generally speaking, sandier soils will need emitters placed more closely to the plant (about 4” from the stem), and will require shorter but more frequent watering.

How to Water

Grouping plants together that have similar water needs on a separate irrigation valve is called “hydrozoning”, and will make irrigation much easier. You can check the relative water needs by searching the Water Use Classification of Landscape Species (WUCOLS) database.

Each irrigation system has its advantages and disadvantages.

- Using a hose can be very effective and enjoyable, although in heavier soils the water may run off the surface without penetrating into the root zone. Pulling a hose through the landscape can damage plants, and the system is difficult to automate.

- Drip irrigation is highly efficient, placing the water at distinct locations around the plant. Runoff, evaporation, and weed growth are minimized, but it does restrict the plant to growing roots only where the drip emitters supply water. Although the system is generally reliable, it is difficult to know when a problem develops.

photo by Jon Kanagy - Micro irrigation uses the same low pressure water lines as a drip system, but has small sprinklers that spray water over a limited area. Some evaporative loss will occur, and the spray pattern is easily disrupted by wind, or the plant itself as it grows into the area of the spray pattern. Many plants do appreciate an occasional overhead sprinkling to wash off dust and help hydrate leaves. Micro irrigation and drip systems are easily automated with timers.

- Sprinkler irrigation. Conventional high pressure sprinklers have the advantage of uniformly wetting the soil, but often waste lots of water to evaporation and overspray onto impermeable surfaces. Since all of the soil surface is watered, weeds are given lots of opportunity to grow. This is generally the least preferred system.

Smart Irrigation Systems

Smart Irrigation Systems

Weather-based irrigation controllers allow for accurate, customized irrigation by automatically adjusting the schedule and amount of water in response to changing weather conditions. Similarly, a soil moisture sensor measures soil moisture content in the active root zone on your property and will adjust irrigation amounts accordingly.

Native Plants

California native plants are not only beautiful, they simply provide critical supplies of food and habitat for our native pollinators and other insects and wildlife. Providing food for insects is critical, since so many birds, bats, reptiles, amphibians and other wildlife depend on them for their survival. For example, California oaks are known to support more than 5,000 species of insects and other invertebrates, far outpacing the contribution from non-native species. In addition, native plants:

- Are well adapted to the California climate, and will exhibit healthy, well-hydrated growth with less water than most non-native species

- Provide a “sense of place” connecting the home gardener to the broader California landscape

- Support local ecology. As development replaces natural habitats, planting gardens, parks, and roadsides with California native plants can help provide an important “bridge” to nearby remaining wildlands.

- Contribute beauty and delight to the community with tremendous diversity in plant form, flowers, and scents

Require less maintenance. While no landscape is maintenance free, many gardeners find that California native plants require significantly less time and resources than common non-native garden plants. California native plants do best with some attention and care in a garden setting, but you can look forward to using less water, little to no fertilizer, little to no pesticides, less pruning, and less of your time.

Require less maintenance. While no landscape is maintenance free, many gardeners find that California native plants require significantly less time and resources than common non-native garden plants. California native plants do best with some attention and care in a garden setting, but you can look forward to using less water, little to no fertilizer, little to no pesticides, less pruning, and less of your time.

The Native “Soil Keepers”

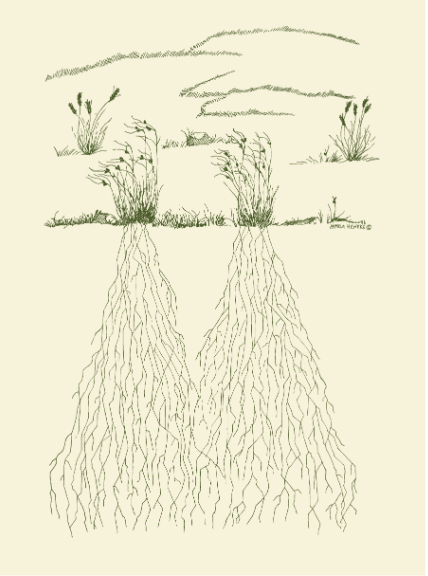

If you live in the Wildland Urban Interface, there is a chance you are surrounded by hills or uneven terrain. To help avoid erosion and runoff on your property, put in some native plants to stabilize the soils, control erosion and reduce your future irrigation costs. Moist and cool months are ideal to start these “soil keepers”. Once established they will require little irrigation. A mixture of plants is best, with various root depths to hold up a slope.

Many native bunchgrasses, for example, have extensive, fibrous root systems reaching many feet in depth. Additionally, many of these perennial grasses, such as our California state grass, purple needlegrass (Stipa pulchra), are long-lived–up to 200 years. It’s interesting to think of a stand of native grasses as having the permanence and resilience of a forest!

Plant Communities

Plant Communities

It is very useful to consider local plant communities near you when selecting plants for your garden. Plant communities are groups of plants that grow together because of similar adaptations to microclimate, rainfall, soil, slope, and other factors, and knowing what grows naturally around you can give insight into plants appropriate for your home landscape. Some plant communities typically found in Sonoma County are:

-

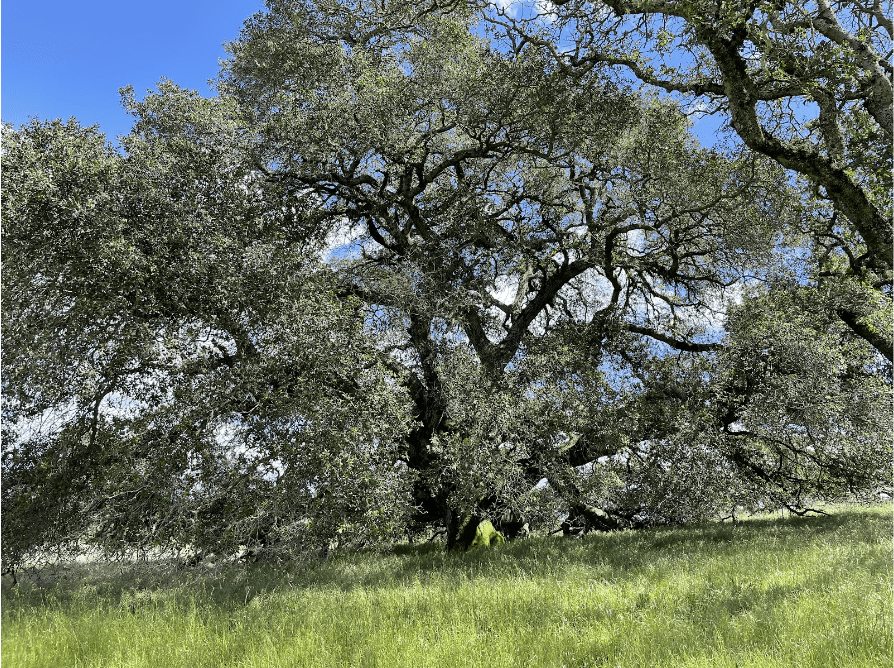

Oak woodland, photo by Jon Kanagy Oak woodland or savanna: An oak savanna is characterized by trees that are widely spaced, often with grassland between, while an oak woodland is characterized by trees growing closer together with canopies often touching. Coast live oak (Quercus agrifolia), blue oak (Quercus douglasii) and black oak (Quercus kelloggii) are dominant species in Sonoma County. The understory can be sparse or more dense with a diversity of shrubs, depending on how much shade the oaks provide. Some oak woodland understory plants are: blue wildrye (Elymus glaucus), California honeysuckle (Lonicera hispidula), iris (Iris douglasiana), California Melic (Melica torreyana), and wooly sunflower (Eriophyllum lanatum). Northern oak woodlands are occupied by many birds but most conspicuously by the acorn woodpecker. A very gregarious bird, the acorn woodpecker lives in large, extended, talkative families collecting and storing acorns.

-

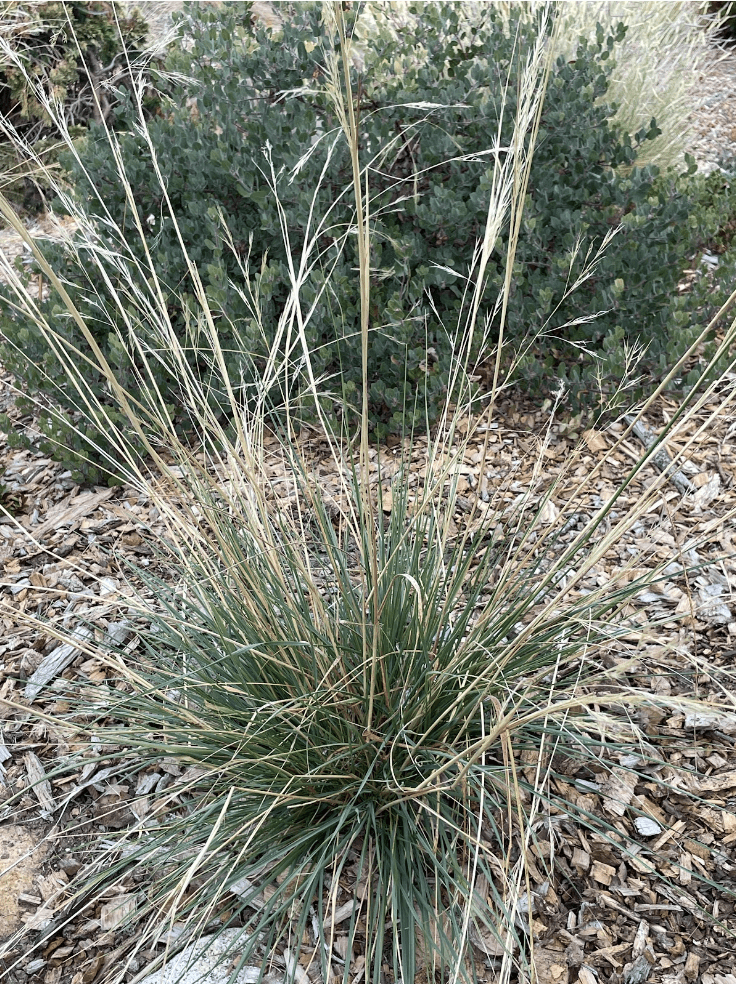

Grassland, photo by Jon Kanagy Grassland plant community: this plant community is composed of perennial bunch grasses, annual grasses, sedges and rushes as well as legumes, like lupine, and other wildflowers. These plants also occur in oak woodlands in open areas among trees.

-

Chaparral, photo by Ellie Insley Chaparral or coastal sage scrub: Chaparral often occurs on west-facing slopes which typically are hotter and drier, and feature few trees, but exhibit very drought tolerant shrubs with hard waxy evergreen leaves or needles. It is a myth that chaparral is “born to burn”, and its natural fire return interval is, in fact, 30 to 150 years. Coastal sage scrub, found on the cooler, moister coastal climates, features soft-leaved, summer-dormant shrubs. Coyote bush (Baccharis pilularis) is a common component of both chaparral and coastal sage scrub, and is a very important habitat plant. Dwarf varieties of coyote bush make an excellent groundcover in the landscape.

- Riparian Woodland: The riparian plant community is found along streams. Common plants include spicebush (Calycanthus occidentalis), willow (Salix species), dogwood (Cornus sericea), white alder (Alnus rhombifolia), big leaf maple (Acer macrophyllum), box elder (Acer negundo), Oregon ash (Fraxinus latifolia), valley oak (Quercus lobata), black walnut (Juglans nigra) and cottonwood (Populus fremontii). Riparian plants are generally more water-loving than those of the other California plant communities. Riparian habitat runs through other plant communities, as water flows through the watershed.

- Redwood forest: This plant community is found along the ocean side of the coast ranges of Northern California. Common species include coast redwood (Sequoia sempervirens), Douglas fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii), California rose-bay (Rhododendron macrophyllum), Western azalea, (Rhododendron occidentale) and tanbark oak (Notholithocarpus densiflorus), The keystone species of the redwood forest, the coast redwood tree (Sequoia sempervirens), can live for more than a thousand years.

-

Mixed evergreen forest, photo by Ellie Insley Mixed evergreen forest: This plant community is found mostly in the northern coastal mountains of California, and usually occupies the cooler, damper north-east facing slopes. Some of the component species include tanbark oak (Notholithocarpus densiflorus), madrone (Arbutus menziesii), Douglas fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii), California bay (Umbellularia californica), bigleaf maple (Acer macrophyllum), canyon live oak (Quercus chrysolepis), black oak (Quercus kelloggii), coast live oak (Quercus agrifolia) and California hazelnut (Corylus californica). This forest is filled with leafy trees and fewer conifers.

Invasive Species

Fire and Invasive Plants

Invasive plants such as English ivy, French broom, and Acacia, are non-native species that cause ecological or economic harm, and are one of the great threats to the health of California’s Wildland-Urban Interface (WUI) areas. In natural plant communities, the presence of invasive plants can increase the risk of wildfire. For example, invasive shrubs like broom (French broom, Genista monspessulana and Scotch broom, Cytisus scoparius) produce a great deal of fine-textured biomass that burns readily and may provide a “ladder fuel” leading fire up into the canopies of trees. Common annual non-native grasses are dry by summertime and create very easily ignited, “flashy” fuels.

Invasive plants such as English ivy, French broom, and Acacia, are non-native species that cause ecological or economic harm, and are one of the great threats to the health of California’s Wildland-Urban Interface (WUI) areas. In natural plant communities, the presence of invasive plants can increase the risk of wildfire. For example, invasive shrubs like broom (French broom, Genista monspessulana and Scotch broom, Cytisus scoparius) produce a great deal of fine-textured biomass that burns readily and may provide a “ladder fuel” leading fire up into the canopies of trees. Common annual non-native grasses are dry by summertime and create very easily ignited, “flashy” fuels.

Invasive plants and wildland health

Most plants don’t escape our yards and gardens, but the handful that do can cause serious problems. Animals, wind, and water move plants and seeds far from where they were planted. Once established in natural areas, these plants displace native vegetation and greatly reduce wildlife diversity. Invasive plants also fuel wildfires, contribute to soil erosion, clog streams and rivers, and increase flooding. Because they thrive in disturbed soils, improper clearance or over-clearance often lead to a landscape dominated by invasive plants. These plants can produce more fuels than native vegetation, increasing the potential for ignition.

How to recognize invasive species?

How to recognize invasive species?

When choosing plants for your fire-safe landscape, you can help protect the health of neighboring wildlands by avoiding invasive species. You can find a full list of invasive species developed by the California Invasive Plant Council. Remember when buying plants to make sure to check the scientific name so that you are getting the species you want! Common invasive plants in Northern California landscapes and wildlands include English ivy (Hedera helix), Algerian ivy (Hedera canariensis), Vinca/periwinkle (Vinca major), pampas grass (Cortaderia selloana), pride-of-madeira (Echium candicans), Himalayan blackberry (Rubus armeniacus), French broom (Genista monspessulana) and Scotch broom (Cytisus scoparius).

Resources

Cal-IPC – California Invasive Plant Council

PlantRight – How to Plant Right

Cal-IPC (2018) – Invasive Plant Checklist for California Landscaping

Importance of Oak Woodland

Oak trees (Quercus spp.) are recognized as significant historical, aesthetic, and ecological resources in California. There are 40 species of native oaks found throughout California on approximately 20 million acres in widely different areas: the central valley, lower foothills, mixed coniferous zone and coastal mountains. Not only are oak woodlands beautiful, they are surprisingly productive communities. More than 330 species of animals (and thousands of insect species!) use oak habitats for some part of the year. As with almost all natural habitats in California, oak woodlands currently face a number of threats and uncertainties. These include concerns about poor regeneration, competition from invasive species, native and introduced pests, habitat loss, changes in land use, threats from fire, and climate changes.

Oak Trees and Fire

Oaks are integral to California’s native ecosystems, making the health and survival of our native oak species particularly important. Fortunately, oaks have evolved mechanisms to survive periodic burning, since fire is a natural element of oak ecosystems. With low- and even moderate-intensity fires that scorch all the leaves on native oaks, little or no long-term damage typically occurs. Even fully burned oaks often will re-sprout and recover over time. When fires occur in the summer and fall, native oaks usually will not produce a set of new leaves until the following spring. Following such fires the trees may appear dead, since all the leaves are brown and brittle and the trunks may be blackened. Many of these trees will survive.

Some oak species are reported to be less prone to ignition than many common non-native trees including eucalyptus, pepper trees and some pines. The large full canopy of oak trees can catch and deflect embers.

Re Oak California

California’s oaks are the powerhouses of our ecosystems, but disease and habitat destruction have put oak populations in serious decline. Now, Californians are coming together to restore this vital natural resource. With a few simple actions, you too can be part of the solution. Consider planting an oak (or a collection of oaks) on your property with locally appropriate oak species. Often, the local Resource Conservation District or local chapter of the California Native Plant Society have volunteer projects to plant acorns and care for seedling oaks. Find your local Resource Conservation District here, and your local chapter of the California Native Plant Society here.

Oak Tree Ordinances

Oak Tree Ordinances

Many jurisdictions in California, including Sonoma County, have Oak Tree Ordinances, and may have other protections for trees and their related plant communities. Check with your local municipality for information about protected trees, and permitting that may be required before removal, pruning, grading, or excavation with the root zone.

Resources

California Native Plant Society – ReOak, Restoring California’s native oak trees

California Native Plant Society – Fire Recovery Guide

California Association of Resource Conservation Districts – Find Your Local RCD

University of California Cooperative Extension – Urban Oak Care

University of California Cooperative Extension – Protecting Homes from Wildfire in Oak Woodlands

University of California Cooperative Extension – The Cultural Values of Oaks

Pest Management

What is Integrated Pest Management (IPM)?

Insects, diseases, and weeds threaten California’s natural environments as well as homes, gardens, and agriculture. This page contains links to articles, fact sheets, and other information prepared by UC scientists on topics related to pests in natural environments.

Integrated Pest Management -or IPM- is an ecosystem-based strategy that gardeners can use to solve pest problems while minimizing risks to people and the environment. A fundamental concept of IPM is that a limited amount of pest damage to plants can be tolerated. Home gardeners using IPM strategies are usually willing to accept minor insect damage to avoid pesticide application. It’s good to remember that insects play a huge role in food webs, and are a tremendous food source for birds and other wildlife.

The University of California defines IPM as:

“An ecosystem-based strategy that focuses on long-term prevention of pests or their damage through a combination of techniques such as biological control, habitat manipulation, modification of cultural practices, and use of resistant varieties. Pesticides are used only after monitoring indicates they are needed according to established guidelines, and treatments are made with the goal of removing only the target organism. Pest control materials are selected and applied in a manner that minimizes risks to human health, beneficial and nontarget organisms, and the environment.”

Integrated Pest Management Recommendations

Identify your pest

Pest identification is always the first step in IPM. The University of California has developed resources to help gardeners identify their pests and find the most effective and sustainable treatment methods. Consult the pages below if you need help with pest identification:

Weed management

All plant pests contribute to fire risk in the landscape as they weaken or kill plant parts. Weeds, however, are themselves flammable and special attention to weed management is needed.

In California, many landscape weeds become established in the winter, as their seeds germinate with winter rain. Most annual weeds will complete their life cycle by spring or summer, when they die and become dry and easily ignitable. In wildlands and parts of the landscape that are less intensively managed, larger invasive weedy vines, shrubs, and trees may create special weed problems. See our Invasive species section for more information.

Weed management strategies

Exclusion

Most weeds spread by seeds, and many common weeds can produce hundreds of thousands of seeds per plant! It may seem daunting, but a “zero tolerance” approach to weeds, preventing them from setting seed, will definitely pay off over time. Seeds will always blow in from the surrounding area, but near total exclusion for a few years will make weed control much easier in the future.

Hand weeding and cultivation

Hand weeding and cultivation

Hand weeding is an ancient weed control method, and many tools help to make the job easier, including garden hoes, shovels, and hand weeders. Many find a “hula hoe” to be a valuable addition to the tool shed. Hand weeding and most other forms of weed control are much easier when weeds are young seedlings. With a small root system they’re much easier to pull or dislodge. While hand weeding in the winter season is important, weeds removed and left laying on the soil surface may reroot in damp weather before they die completely. While it’s possible to use weeding tools in areas covered by wood mulch and small gravel, larger gravel and cobble can not be hoed. Likewise, the use of weed fabric makes mechanical weeding difficult.

Mulching can be a great way to reduce weed pressure and has many other benefits. See our Mulch section for more information. (link to Mulch)

Flaming

Flaming is the use of a handheld propane torch to kill weeds by heating them and causing the cells to burst. It should be used with great care and is most appropriate for use during very damp winter weather. Flaming is not recommended during fire season or at under any circumstances when fire may escape control. Despite the high heat produced, the best effects are with weeds that are at a very small seedling stage. It can be a particularly useful tool for removing weeds from areas of gravel and rock, and in spaces between patio and walkway pavers.

Herbicides

Herbicides

The use of synthetic herbicides in home landscapes should be very limited given the risks they present to humans and the environment, and we do not recommend their use. Organic herbicides, often based on vinegar and certain essential oils, don’t persist in the environment, but should still be used with caution as they can injure the eyes and skin. Many find that organic herbicides work best with very young seedlings, and they will cause damage if they contact desirable plants.

Mulch

Mulching with wood chips, photo by Jon Kanagy

Mulch is any material used to cover the soil, and offers many benefits in a landscape. It can:

Mulch is any material used to cover the soil, and offers many benefits in a landscape. It can:

- Reduce the occurrence of weeds

- Reduce evaporation of water from the soil, leaving more for plants

- Keep soil temperatures cooler, which is important for plant roots and beneficial soil organisms including earthworms

- Help control soil erosion from rainfall and wind

- Prevent soil compaction, allowing more air to enter the soil for healthy plants and soil life

- Slowly decompose and contribute valuable organic matter to the soil, if a plant-based mulch is chosen

- Visually enhance the landscape

Using mulch in a firewise landscape

Adjacent to homes and other structures, in a zone 0-5’ from the walls, only inorganic mulch such as gravel and rock are recommended. In a zone 5-30’ from homes and other structures, plant-based mulches such as wood chips and bark may be used to a depth not more than 2-3”. Since all plant-based mulches are combustible, they should not be used in a widespread or continuous manner. Islands of plants can have wood mulch underneath, but the groupings of plants should be separated by some pathways or other features that utilize non-combustible materials. Note that larger sizes of gravel and rock do not allow weeding tools to be used, thus reducing the options for weed control to hand pulling (or herbicides). Wherever organic mulch is used, it should be kept a few inches away from the bases of taller shrubs and trees.

Leaf litter provides a valuable free mulch that is highly beneficial to plants and soil. As leaf litter can be flammable, it should be kept to 1” or less in Zone 1 in the dry season, but allowed to accumulate to enrich the soil in winter In zone 2, it may remain year ‘round but not allowed to accumulate to more than a few inches. It’s important to continually remove any leaf litter or other debris within 5’ of the structure.

Weed barrier fabric and plastic

Weed fabric and plastic sheeting are also types of mulch typically used under gravel and bark. They do, however, have many disadvantages and are not recommended. Before long, weed seeds begin to germinate in the mulch on top of the barrier, and their roots will tear it when pulled. Loose fabric and plastic is an eyesore and difficult to bury once it becomes exposed. Most importantly, weed barrier fabrics and plastic exclude earthworm and microorganism activity, leading to dead, compacted soils. A weed barrier that may have a place in the weed management arsenal is cardboard. Cardboard sheets, especially when used in the late fall or winter and covered with 2-3” of wood chips, will provide great weed control and the cardboard will be largely decomposed by the following summer. This technique is called sheet mulching and is also a great way to convert a lawn into a new, native landscape.

We appreciate the contributors to this section:

California Flora Nursery

Calscape.org

Sources:

UC Master Gardener Program of Sonoma County, California Natives

Marin Chapter, California Native Plant Society Plant Replacement List

California Flora Nursery

Calscape, a native plant database from the California Native Plant Society